|

ITINERARIES

– Itinerary 1 (part one)

by Gustavo Cannizzaro

The

High Area “Susu”

|

|

The

starting point for a visit to the Historical Centre of Caulonia

has to be Piazza Umberto I, alias Mese.

Such a toponym can be clearly deduced

from the Greek word “Mesos” (centre, in the middle).

Taking a closer look at the town planning, the characteristic

medieval town layout springs to the eye.

The

towns with a certain importance had three ample, open spaces

or squares for civil and religious purposes. Caulonia has Piano

Baglio up at the top which was the trading centre, Piazza Seggio

at the bottom which was the political centre and between these

two there is Piazza Mese, which, even today represents the religious

centre with its Chiesa Matrice (this is the square where the

suggestive rites of the Holy Week are held).Structurally,

the square has an irregular shape, it develops on different

levels, which are divided by Via Vincenzo Niutta, and descend

towards the bell tower of the Matrice church. Thanks to this

layout the square has a pleasing and unusual prospective. On

the high area there is an wraught iron fountain dating from

the end of the Ottocento set on a contained granite base. Around

the perimeter of the square there are clusters of houses and

two of the most interesting palaces in Caulonia which belonged

to the nobility; one side of the Hyerace palace and the Ottocento

facade of the Cricelli palace flanked on one side by the church

of the Badia. Recently the road has been paved with Calabrian

granite slabs in substitution of the previous cement. At the

bottom, the square is closed off by the architectural structure

of the Matrice church.

Caulonia |

The

Matrice church “SS. Maria Assunta”

The

architectural structure composed by the church and the bell

tower, still today as it was depicted by Pacichelli in his incision

dating 1703. As well as being one of the architectural emergencies

of the town, is also one of the focal points in the road network

thanks to the covered passageway under the bell tower. There

is very little information about the construction of the church

which was rebuilt in 1513 by Vincenzo Carafa, the second baron

of Castelvetere.

The

church was probably built on an older one, so over the course

of the years it had to undergo various readaptions: in 1637

and after the earthquake in 1783. The tripartite facade with

the bell tower leaning against it is an example of spontaneous

architecture, while the domes, with the characteristic tiled

roofing, are typical of Calabrian sacred constructions belonging

to the 1600s and 1700s. they are clearly inspired by more antique

models of Byzantine origin and in the style of the Cattolica

di Stilo. The construction technique

of these domes respect the basilian architectural tradition

of which there are still traces in the Matrice church and other

buildings such as the old theatre and the ex church of San Leo.

Specifically regarding the Matrice church, observing the difference

in the levels, the difference in size and also the articulate

layout, it seems very probable that some of the domes are not

a late reconstruction from the XVII and XVIII centuries, but

belong to the original structure from the previous century.

The main entrance, built in local granite, is surmounted by

the Carafa coat of arms in Carrara marble probably dating from

the beginning of the XVIII century. Inside, the church is composed

of a nave and two side aisles, divided by six pillars. The ceiling

is trussed, following recent restoration work. The XVIII century

wooden pulpit is still under the right hand median archway of

the nave. The walnut benches sit in the apse where a written

note on the high part of it states their being made in 1757

commissioned by the archpriest Annibale Passarelli. Below this

rises the first baron of his house, Giacomo Carafa’s funerary

monument.

Matrice Church |

Giacomo

Carafa’s Funerary Monument

|

|

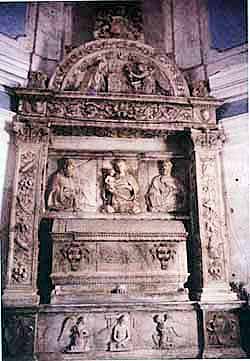

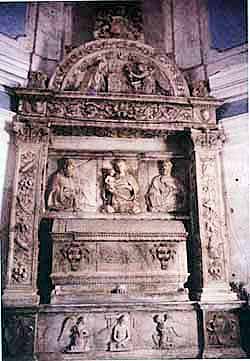

The

monument is sculpted in white marble and follows a linear renaissance

architectural style composed of a predella, two architraved

pillars and a half moon flanked by two marble bases which used

to bear vases. The Vases were transported to the vescovial residence

of Gerace towards the end of the 1800s and have subsequently

disappeared. The predella holds the traditional depiction of

Christ, dead and with the symbols of passion, flanked by two

adoring angels. The sarcophagus is between the pillars and above

it are three panels one with the Madonna and child, another

with Saint Peter and one with Saint Andrew. The half moon contains

the Annunciation scene. The heraldic symbols of the Carafa della

Spina family are sculpted on the bases of the pillars.

From the epitaph

inscribed on the sarcophagus we know that the monument was commissioned

for Giacomo Carafa, who died in 1489, by his son Vincenzo. Another

epitaph from 1637 states that the monument was restored on commission

of Girolamo Carafa, IV Marquis of Castelvetere. This monument,

whose creator is unknown, follows the renaissance funerary monument’s

model which originated in Florence and spread throughout Italy

acquiring small variations from region to region. Its conographic

structure shows a clear derivation from Neapolitan and Sicillian

models.

The decorative parts such as the frieze on the architrave, the

candelabrums, the fruit garlands and the weapons in all their

refined variations, are a testimonial of great artistic virtue

and a rare and refined chiaroscuro which echoes Lombardia style

decorations, brought to southern Italy by Domenico Gagini and

subsequently widely spread by his son Antonello and his scholars.

It is not a chance that the garlands of fruit, flowers and weapons

are similar to those by Antonello Gagini and his scholars in

the Duomo di Palermo. Also the sculptures belonging to the monument,

once multicoloured and golden, have Gagini’s style: the Madonna’s

face, smooth and light, with eyes downcast, slight smile and

with two strands of hair framing her face. It is similar to

the Madonna called “Annunziata” belonging to the Gancia church

of Palermo, also sculpted by Antonello around 1516. The same

applies for the Annunciation depicted in the half moon, it is

similar to that in the Erice museum dating 1525. Finally, the

Christ in the predella has close analogies with the “Cristo

morto” in the archipriest’s church in Soverato Superiore, traditionally

recognised as Gagini’s work. Taking into account all these stylistic

traits so similar to those of the Sicilian sculptor between

1516 and 1525, it is possible to take into consideration that

the monument belongs to the second half of the XVI century.

This finds confirmation in the fact that the church was built

between 1513 and 1517, therefor it is possible that the monument

was a part of the reconstruction project.The chapel of the Sacred

Heart is at the end of the left aisle. It has a balustrade and

an altar in blended marble, typical 1700’s taste, created in

1766, commissioned by Vincenzo Sergio, a Castelvetere patrician

whose coat of arms are sculpted on the sides of the frontal.

Also the vault is of interest, decorated in white, gold and

coloured stucco with four panels featuring the evangelists.

The entire decoration, which is in great disrepair, is probably

the work of local artists of the XIX century. The chapel of

Saint Ilarione is in the right aisle and it presents a decoration

in golden stucco following the neo gothic taste of the last

century.

On the right, in a niche,

we

find the wooden statue of the Patron Saint of Caulonia made

by a Serrese artist in 1815.

The sculpture must be

considered important, apart from its religious connotations,

for the historical-cultural aspect it represents. It reminds

us how the history of Greek Christianity was followed by Latin

Christian rites. Saint Ilarione is an Eastern saint who is celebrated

in the Greek Orthodox liturgy on the 21st of October,

the same date as in the Catholic calendar. The followers of

the Greek religion would certainly have represented the saint

in the shape of an icon, never as a sculpture which is three

dimensional (we must remember that Byzantine world fought the

iconoclastic wars).It must therefor be underlined that the icon

is a hieratic and immaterial representation of the sacred image,

while the sculpture, by nature is more corpulent.

we

find the wooden statue of the Patron Saint of Caulonia made

by a Serrese artist in 1815.

The sculpture must be

considered important, apart from its religious connotations,

for the historical-cultural aspect it represents. It reminds

us how the history of Greek Christianity was followed by Latin

Christian rites. Saint Ilarione is an Eastern saint who is celebrated

in the Greek Orthodox liturgy on the 21st of October,

the same date as in the Catholic calendar. The followers of

the Greek religion would certainly have represented the saint

in the shape of an icon, never as a sculpture which is three

dimensional (we must remember that Byzantine world fought the

iconoclastic wars).It must therefor be underlined that the icon

is a hieratic and immaterial representation of the sacred image,

while the sculpture, by nature is more corpulent.

The Byzantine world had educated us in the tradition of icons;

it was the Normans and the Spaniards who introduced us to the

tradition of sculpture. That is why the wooden statue of Saint

Ilarione, seen in a syncretic context of ancient and modern

rites, assumes an important historical value for us. The

church also holds an interesting organ (very damaged) with indipendent

resonance boxes, registers with pommel stay-rods, “window”

keyboard and encased pedals. The date of construction,1762,

is on the keyboard. This organ, thankfully restored seeing its

rarity, could be used to play Renaissance and Baroque music

as originally written, without modifications.

Among the silver decorations,

the relic arm of saint Ilarione and the calyx and the monstrance

are important. The arm was a gift from the Carafa house. Their

coat of arms is lightly inscribed in the base also as the family

had the “jus patronato” over the church.The sobriety of the

object’s decoration reveals the tendency to develop simple shapes

and lines which was popular among Neapolitan silversmiths since

the first half of the 1600’s.

The calyx was donated to the church by

the archpriest A. Passarelli in 1745, the inscription at its

base is still visible. This object with a Neapolitan consular

piercing inscribed on it is of excellent quality. It is a beautiful

sample of Rococo taste with its rich and elegant decorations.

The monstrance, commissioned by Vincenzo Maria Carafa in 1804

to a Neapolitan silversmith, was fashioned by hollow casting

and chiselling; it was made in the neo-classic period but its

style is anchored to the 1700s. Exiting the church, one must

walk through the square up to the high area where the entrance

of the Badia is found.

|